Natalie Munro, University of Connecticut

This holiday season millions of families will come together to celebrate their respective festivals and engage in myriad rituals. These may include exchanging gifts, singing songs, giving thanks, and most importantly, preparing and consuming the holiday feast.

Archaeological evidence shows that such communally shared meals have long been vital components of human rituals. My colleague Leore Grosman and I discovered the earliest evidence of a ritual feast at a 12,000-year-old archaeological site in northern Israel and learned how feasts came to be integral components of modern-day ritual practice.

First, what are rituals?

Rituals involve meaningful, often repeated actions. In modern-day practices they are expressed through rites such as the hooding of a doctoral student, birthdays, weddings or even sipping wine at Holy Communion or lighting Hanukkah candles.

Pompeii family feast painting, Naples.

Unknown painter before 79 AD, via Wikimedia Commons

Ritual practice may have emerged along with other early modern human behaviors more than 100,000 years ago. However, proving this with material evidence is a challenge. For example, researchers have found that both Neanderthals and early modern humans buried their dead, but scholars weren’t certain whether this was for spiritual or symbolic reasons and not for something more mundane like maintaining site hygiene. Likewise, the discovery of 100,000-year-old symbolic artifacts like pierced shell ornaments and decorated chunks of red ochre in caves in South Africa, was not sufficient to prove that they were part of any ritual activities.

It was only when archaeologists found these artifacts, placed in graves going back 40,000-20,000 years, that it was confirmed they were part of ritual practice.

The first feasts

We had a similar experience during our research. When Leore Grosman and I first embarked on the excavations at Hilazon Tachtit in the late 1990s, we were only hoping to document the activities of the last hunter-gatherers in Israel, at what appeared to be a small campsite. It was only over several seasons of excavation that it slowly became clear to us that this was not a site where people had lived. Rather it was a site for rituals.

Hilazon Tachtit cave interior.

Naftali Hilger, CC BY-NC-ND

No houses, fireplaces or cooking areas were recovered. Instead the cave yielded the skeletal remains of at least 28 individuals interred in three pits and two small structures.

One of these structures contained the complete skeleton of an older woman, who we interpreted as a shaman based on her special treatment at death. Her grave stood apart due to its fine construction – the walls were plastered with clay and inset with flat stone slabs. Even more remarkable was the eclectic array of animal body parts buried alongside of her. The pelvis of a leopard, the wing tip of an eagle, the skulls of two martens and many other unusual body parts surrounded her skeleton.

The butchered remnants of more than 90 tortoises buried in the grave and the leftovers of at least three wild cattle deposited in a second adjacent depression excavated in the cave floor represent the remains of a funeral feast.

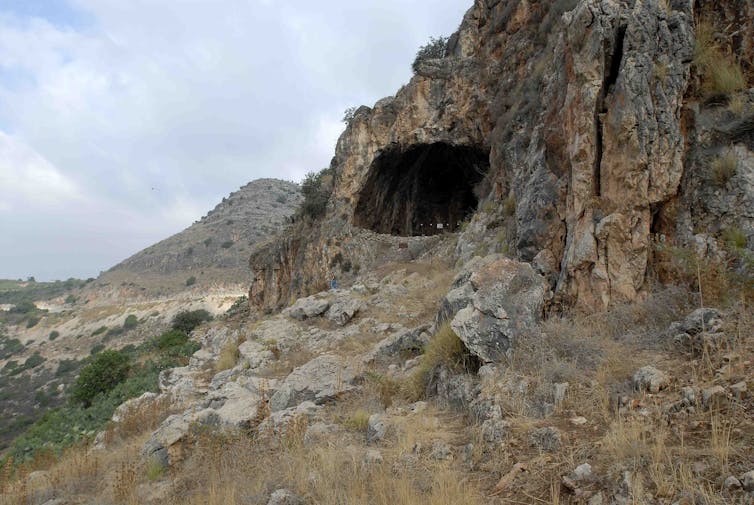

Hilazon Tachtit cave.

Naftali Hilger, CC BY-NC-ND

The outstanding preservation of the grave enabled us to detect multiple phases of a ritual performance that included the consumption of the feast, the burial of the woman, and the filling of the grave in several stages, including the intentional deposition of garbage from the feast.

Feasting at the beginning of agriculture

Archaeologists have found other sites that show evidence of ritual feasting. Many of these date to the time when humans were beginning to farm.

Site of Göbekli Tepe.

Teomancimit (Own work) , via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

One of the most striking is the site of Göbekli Tepe in southeastern Turkey, dating slightly later than Hilazon Tachtit. It includes multiple large structures adorned with benches and giant stone slab carved with exquisite animal depictions in relief dating to 11-12,000 years ago. Perhaps, these were very early communal buildings. The archaeologists who excavated Göbekli Tepe argue that massive quantities of animal bones associated with the structures represent the remains of feasts.

Twelve thousand years ago humans were still hunter-gatherers, subsisting entirely on wild foods. Nevertheless, these people differed from those who went before – they were sitting on the brink of the transition to agriculture, one of the most significant economic, social and ideological transformations in human history.

Sickle blades and grinding stones used to harvest and process cereal grains are found at Hilazon Tachtit and other contemporary archaeological sites. These findings indicate that these ritual feasts started around the same time that people adopted agriculture. When people began to rely more heavily on wild cereals like wheat and barley, they became increasingly tethered to landscapes that were ever more crowded and began to settle into more permanent communities. In other words, feasting became a part of their life, once they moved away from nomadic life.

Rituals that bind

These feasts had an important role to play. Adapting to village life after hundreds of millennia on the move was no simple act. Research on modern hunter-gatherer societies shows that closer contact between neighbors dramatically increased social tensions. New solutions to avoid and repair conflict were critical.

The simultaneous appearance of feasting, communal structures and specialized ritual sites suggest that humans were seeking to solve this problem by engaging the community in ritual practice.

One of the central functions of ritual in these communities was to provide a kind of social glue that bound community members by promoting social cohesion and solidarity. Feasts generate loyalty and commitment to the community’s success. Sharing food is intimate and it builds trust.

Communal rituals would have provided a shared sense of identity at a time when social circles were increasing in scale and permanence. They reinforced new ideologies that emerged out of a dramatic reorganization of economic and social life.

Role of feasts today

Feasting plays the same essential role today. Like the earliest feasts, our holiday celebrations are replete with actions that are repeated year after year.The holiday feast today builds family traditions. By cooking and sharing food together, telling stories of past holidays and exchanging intergenerational wisdom, holiday rituals bond extended families and give them a shared identity.

Natalie Munro, Professor, University of Connecticut

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

No comments:

Post a Comment