Guest Post: Scandinavian winters of old were less hygge, more Nordic Noir

by Hannah Burrows, University of Aberdeen

This winter hygge has replaced Nordic Noir as the UK’s favourite Scandi-import. But the festive season in the Nordic world has not always granted an opportunity for cosy mindfulness. Medieval sources offer a decidedly more terrifying vision of Christmas, or jól (yule), its proximity to the winter solstice putting it at the heart of icy nightmares.

In the tenth century, King Hákon the Good (c. 920-961) ordered that the pre-Christian festival of yule should be observed at the same time Christians celebrated Christmas, Icelandic historian Snorri Sturluson (1179-1241) tells us. The word jól was not replaced when it came to designate the Christian feast and related terms are still used in the modern Scandinavian languages. Both festivals involved drinking and feasting – but Old Norse texts also make a firm correlation between yuletide and the supernatural.

Understandably in such a northern climate, Norse mythology associated wintry weather with hostile forces. It was said that a mighty winter lasting three years would lead up to ragnarök, the apocalypse. The giants that constantly threaten the civilisation of the gods are associated with rime and frozen altitudes – one even has an icicle-beard that tinkles as he moves. It’s no surprise in Game of Thrones that those living north of the Wall are referred to as “wildlings” by the citizens of the Seven Kingdoms, or that the truly terrifying White Walkers come from the “Lands of Always Winter” in the Far North.

Yuletide ghosts

In the Icelandic sagas, hauntings are particularly rife at Christmas, with draugar, the corporeal ghosts of the deceased, returning to wreak havoc in their former households.

In the saga of Grettir Ásmundarson, for example, the fearsome shepherd Glámr engages in a mutually fatal Christmas Eve battle with an “evil creature” beleaguering the farm. But Glámr returns posthumously to damage property and terrorise the population by night. The hauntings lessen as the days grow longer, but next Christmas Eve the cycle begins again. In the third year, the pattern is broken by the eponymous hero Grettir, who – after an almighty tussle – is able to defeat the revenant by cutting off its head and placing it beside its buttocks (though not before being cursed so that Grettir is forever afraid of the dark).

And in The Saga of the People of Eyri (Eyrbyggja saga), a household is beset just before yule by a supernatural seal popping up through the fireplace – a far less welcome visitor than Santa coming down the chimney. Every attempt to club the seal only makes it rise further, until a boy whacks it with a sledgehammer “and the seal went down as if he were driving in a nail”. The ghostly return of six drowned men is at first celebrated, but the revenants outstay their welcome and are eventually dispatched through a combination of religious rites and legal proceedings.

In latitudes where midwinter offers at best four or five hours of daylight, it is natural that beliefs imbued with a fear of the dark should transpire. It has been suggested that the association of revenants with winter may have been heightened because solidly frozen ground or heavy snowdrifts could hamper normal burial procedures, leading to a consequent fear that the dead could more easily rise.

Freaky feasts

Even kings can’t avoid their Christmas parties being ruined by supernatural happenings. In Snorri’s Heimskringla, his chronicle of the kings of Norway, all the food for King Hálfdan’s (c. 810-860) yule banquet is spirited away. King Harald Fine-Hair (c. 850-932), on the other hand, drinks a love-potion disguised as Christmas mead, driving him so mad with desire he neglects his kingly duties until the object of his new affections dies and is cremated.

Aristocratic Christmases are also documented by the skalds, medieval Scandinavia’s court poets. Here we find all the elements now associated with a merry Christmas – eating, drinking and gift-giving – but given a typically dark and martial twist.

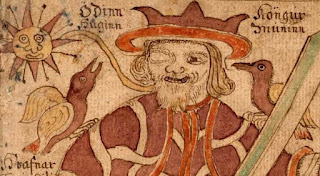

|

| Odin with his ravens Huginn and Muninn |

The medieval period didn’t have a monopoly on creepy Christmases. Iceland’s Grýla may be a giantess known to Norse myth, but her tendency to devour naughty children at Christmastime – and her pet cat who gobbles up those without new clothes – are recorded hundreds of years later. Modern-day figures have become more good-natured, though: Grýla’s sons, known as the “Yule Lads”, are now more likely to be found distributing Christmas gifts than scaring the population into good behaviour.

“Winter is coming” still resounds with menace in modern storytelling, but we can all sleep snug in our beds knowing we probably won’t have to contend with a supernatural seal while hanging the stockings this Christmas.

Hannah Burrows, Lecturer in Scandinavian Studies, University of Aberdeen

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

No comments:

Post a Comment